Atomic Bomb’s Squadron Shrouded in Secrecy

Use controls above or click here to open this Hometown Heroes podcast in a new window

95-year-old Norris Jernigan of Visalia, CA appears on episode #640 of Hometown Heroes, airing August 6-10, 2020, coinciding with the 75th anniversaries of significant dates in the history of the 393rd Bomb Squadron, with which he served.

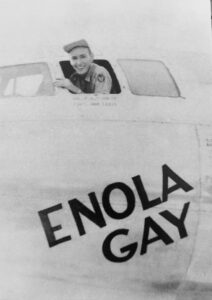

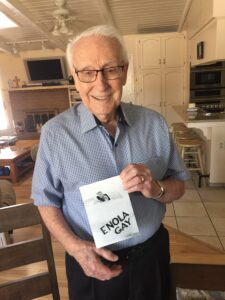

95-year-old Norris Jernigan with a photo of his 20-year-old self in the cockpit of Enola Gay. For more photos, visit the Hometown Heroes facebook page.

On August 6th, 1945, the B-29 Enola Gay, piloted by Paul Tibbets, dropped the first atomic bomb over Hiroshima. Three days later, Bockscar, with Charles Sweeney in command, delivered the second bomb to Nagasaki. Until that week, all Jernigan and most members of the squadron knew is that they were involved with a “secret weapon” that was often referred to as “the gadget” or “the gimmick.” Follow along as Mr. Jernigan takes us from his childhood to his decision to enlist in the Army Air Corps before finishing high school. His earliest memories involve the death of his mother in his native Eugene, OR, before his third birthday. After some time in New Mexico, his family ended up in California, and the formative years for Norris were spent on a 40-acre ranch “out in the boondocks” between Galt and Elk Grove in southern Sacramento County.

“The Great Depression was on then,” you’ll hear Jernigan explain. “That little ranch saw us through the Depression. We, of course, raised almost everything we ate.”

Milking cows, feeding hogs, and tending to 2,000 egg-laying hens kept Norris busy, and he would find himself dreaming about someday getting off the farm and having his own desk and his own office. At Galt HS, he played bassoon in the band and also participated in cheer. On December 7, 1941, 16-year-old Norris learned about Pearl Harbor from a man who was delivering cows to the Jernigan ranch. You’ll hear him remember that moment, as well as what followed, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 paved the way for the incarceration of Japanese-Americans, including many of Jernigan’s high school friends.

“It just completely devastated our football team,” you’ll hear him recall. “Our football team was just reduced to nothing because of such a high percentage of Japanese kids that were in our high school.”

Public perception had turned his friends into his “enemies” almost overnight, and you’ll hear Jernigan describe how his perspective has changed over the years since. As his 18th birthday approached in June, 1943, Norris wanted to enlist in the Navy, as opposed to being drafted into the infantry. His father, who was working at Mare Island Naval Shipyard, objected on the basis of all the remains of sailors he had pulled from the wreckage of vessels under repair. He told Norris that he could instead follow his older brother into the Army Air Corps, and Jernigan left high school at the end of his junior year to join the cadet program, with the dream of becoming a B-17 bomber pilot. He headed to Wichita Falls, TX for basic training at Sheppard Field, followed by a semester at Denver University in Colorado, where he experienced his first ten hours of flight instruction at Hayden Field in Piper Cubs.

“I’d never been in an airplane before,” Jernigan relates. “That first takeoff, it was just so exciting.”

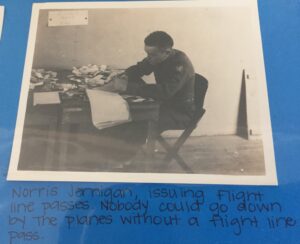

A surplus of flying cadets cost Norris is chance at a cockpit, a bit of unfortunate timing that left him feeling “crushed.” After brief assignments in Santa Ana, CA and Salt Lake City, UT, he was sent to Fairmont, NE, and assigned to the motor pool. When an opening in the intelligence office of the 393rd Bomb Squadron cropped up, his typing proficiency made him a match for the assignment, and he seized the opportunity. By August, 1944, the squadron had completed its training and was ready to head overseas. Instead, it was separated from the 504th Bomb Group and sent to Wendover Field on the Utah/Nevada border. In his second day at Wendover, Norris and the rest of the squadron’s enlisted men were gathered together, and a lieutenant colonel climbed onto the back of a truck to address the crowd.

“I want you to know that you’ve been brought here for a purpose,” Norris remembers Paul Tibbets saying. “You’re going to become part of an organization that’s going to be handling a new secret weapon, that if successful, should shorten the war by at least two years.”

The secrecy of the project was emphasized before Tibbets sent the men home for a 2-week furlough. He described it as an opportunity for rest, but it would eventually become clear that it was a test to see if anyone would compromise the clandestine nature of their endeavor. Listen to Hometown Heroes for a couple of classic examples of how the FBI protected that secrecy, and how hard it was for Norris to avoid any mention of that mission. Norris wouldn’t find out what the secret weapon actually was until after the uranium bomb “Little Boy” was dropped over Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. Since then, he has learned that initial plans provided for using two atomic bombs simultaneously against both Japan and Germany, but that the quicker end to hostilities in Europe made such a move unnecessary.

The squadron was sent to the island of Tinian as part of the 509th Composite Group. While many flew there in B-29s and C-54s, Jernigan was sent via ship. As an intelligence clerk, Norris was responsible for typing reports, and assembling folders of maps, aerial photographs, and other information the officers would need. Daily teletype transmissions would give him the locations of submarines, ships, and amphibious planes, so Jernigan could pass that information on to flight crews in the event they were unable to return to Tinian.

“Around August 1st, we realized that things were starting to happen because all of a sudden, people started showing up,” you’ll hear Norris explain. “Civilians showing up, a lot of high-ranking officers showing up, even a naval officer showing up.”

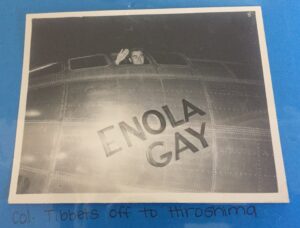

The sight of armed military policeman guarding the doors to the chapel meant secret meetings were taking place inside, a buzz was building, and soon Norris was aware that August 6th would become the date that Paul Tibbets and his B-29 crew would make history. You may have known that Enola Gay was named after Tibbets’ mother, but you’ll hear Jernigan detail the special aviation-related reason behind that. You’ll also hear why Norris wasn’t there in person to see the legendary pilot pose for the now famous photo that features the face of Tibbets protruding from the side cockpit window. The smile on the waving aviator’s face gives no indication of what Norris calls the feeling of “awesome responsibility” that motivated Tibbets to invoke his rank as squadron commander to bump Captain Robert Lewis to the co-pilot’s seat.

“They had no idea whether that airplane could leave the area in time to not be blown apart with the bomb, even at 30,000 feet” Jernigan says of that groundbreaking mission. “He wasn’t going to ask somebody else to do something that he wouldn’t do himself.”

August 6th produced a holiday atmosphere on Tinian, where everyone knew that something significant was happening. A picnic complete with carnival games entertained the men until the Enola Gay returned from its fateful mission to Hiroshima. After the crew completed its post-mission interrogation, Tibbets interrupted the picnicking crowd with an announcement.

“Successful mission,” Norris remembers his commander saying. “Sighted city, destroyed same.”

Norris Jernigan and some friends later went to pose for their own photos in Enola Gay, peeking out the same side cockpit window that Tibbets had made famous. Consensus on Tinian was that Imperial Japan would immediately capitulate, but when that did not happen, another nuclear weapon laden mission launched on August 9th, 1945. Bocskcar, piloted by Charles Sweeney, carried the bomb “Fat Man,” powered by a plutonium core. The city of Kokura was the primary target, but cloud cover spared it from the fate that secondary target Nagasaki would suffer. The reality that two entire cities had been virtually destroyed, with the threat of other cities facing that threat, helped convince Japan to unconditionally surrender on August 14th. The planned Allied invasion of Japan was no longer necessary, so the estimated casualties of one million Americans in the initial stages of that effort, and several times that on the enemy side, became hypothetical instead of historic. Over the years, Jernigan has heard some suggest that the atomic bombs were unnecessary. He remains convinced they shortened the war considerably and saved millions of lives on both sides.

“It had to be done. That was the reason it was developed. That was the reason it was used, and the use of it stopped the war,” you’ll hear him state. “I’m glad they were dropped, no question about it. I’m glad they’ve never been used again. I hope they never will be.”

Watch the video below for more of Mr. Jernigan’s thoughts on the atomic bomb, 75 years after he first learned the identity of that “secret weapon.” That childhood ambition of having his own office and desk would come true after he used the G.I. Bill to attend college (American River College & CSU-Sacramento) and became an accountant, enjoying a long career as the office manager for Kaweah Construction in Visalia, where he has lived since 1970. When asked what brings him the most pride at age 95, you’ll hear him turn immediately to his marriage. Norris and Marilyn two weeks after his discharge from the Army Air Corps. They enjoyed 68 years of marriage before her passing in 2015.

—Paul Loeffler