Living History, Preserving History

Use controls above or click here to open this Hometown Heroes podcast in a new window

91-year-old Murray Lee of San Diego appears on episode #528 of Hometown Heroes, airing June 14-17, 2018. Born on a Michigan farm, raised in Detroit and Washington, D.C., Lee served in the U.S. Merchant Marine before becoming an accomplished cartographer and historian.

Murray Lee as a teenager in the U.S. Merchant Marine. For more photos, visit the Hometown Heroes facebook page.

Murray’s mother was caucasian, while his father was the son of Chinese immigrants. During the Great Depression, his father realized that the government presence in Washington, D.C. would make it a good place to find work, even during that economic drought. You’ll hear Murray remember that there were “no Asians at all” in Arlington County, VA, where the family settled. Competing in the pole vault, half-mile race, and broad jump for the Generals of Washington-Lee High School in Arlington, Murray remembers his teenage years being altered by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and America’s entry into World War II.

“Everybody knew that they had to go in the service as soon as they graduated,” you’ll hear him explain.

At the time, he hadn’t personally experienced much discrimination with regard to his Chinese heritage. Lee’s research in later years, particularly for his book Through the Eyes of Heroes, chronicling the contributions of Chinese-American veterans, brought him familiarity with some of the difficult realities faced by Asian-Americans during this era.

The military had restrictions on what positions Asian-Americans were allowed to hold, and the reactions to Japanese-Americans in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor had many in San Diego’s Chinatown area taking precautionary measures. “I AM CHINESE,” read notes affixed to their jackets.

“A lot of people can’t tell the difference between Chinese and Japanese,” Lee explains. “If they saw you and thought you were Japanese, they might beat you up.”

In San Diego, Chinese and Japanese families lived in close proximity to each other, and Lee’s research presented multiple example of Chinese-Americans offering to maintain and protect businesses and property for Japanese-Americans when Executive Order 9066 forced them into internment camps. Murray had two older half-brothers who were among the first Chinese-Americans to enlist after the attack on Pearl Harbor, both serving in the Army Air Corps. One of them even survived parachuting out of a crippled C-46 while flying “The Hump” over the Himalayas between China and India. The pilot was killed while keeping the plane steady enough the 20 other men to jump, while the survivors – including legendary CBS newsman Eric Sevareid – encountered a headhunting cadre of Naga warriors in the Burmese jungle. The story of their month-long ordeal is told in Robert Lyman’s 2016 book Among the Headhunters.

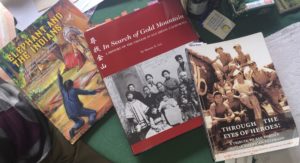

Three books that Murray has published. He’s working on a fourth. Click here for an article about his work from the Voice of San Diego.

Murray’s personal World War II story, which is included in Through the Eyes of Heroes, starts with a high school classmate suggesting they join the U.S. Merchant Marine. After training in Sheepshead Bay, NY, he was sent to Norfolk, VA and assigned to a merchant vessel in need of crewmen.

“I know why they were looking for people because they couldn’t keep them,” Lee says of the ship, which had been built in 1916. “It didn’t have a bit of paint on it, it was 100% rust.”

Murray is proud to have his plaque on display at the Mt. Soledad National Veterans Memorial.

The 18-year-old had never steered a ship before, but soon demonstrated his dexterity as a helmsman. You’ll hear Murray explain how he ended up in New York City’s Times Square on V-J Day, witnessing in person the pandemonium that has become exemplified by the image of a sailor smooching a nurse. Whenever he sees San Diego’s larger-than-life statue capturing that kiss, he’s reminded that he was a little too bashful to attempt something that brazen on August 14, 1945. Lee is quick to point out that the end of hostilities did not equate to the end of dangerous situations for him.

“When we were out in the Atlantic, we had to watch out for floating mines,” he explains.

Serving on both Liberty ships and Victory ships, he made several more journeys, delivering cargo as well as bringing troops home from Europe. One voyage, with the Liberty ship SS Thomas Sumter carrying raw sugar from Cuba to Europe, nearly turned tragic when the engines quit in the middle of the North Atlantic. Adrift for four days, with one rescue attempt failing because the tow rope snapped, the ship finally started moving again when someone decided to burn some of the sugar to reignite the engines.

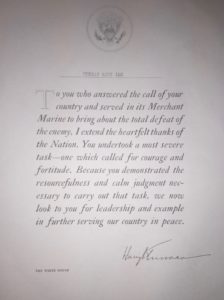

Murray was one of more than 240,000 Merchant Mariners who received the gratitude of President Harry Truman, but were never eligible for veterans’ benefits until 1988.

You’ll hear Murray share other anecdotes from his Merchant Marine years, including a trip to Argentina that brought him face-to-face with a Gestapo-esque guard who confiscated the knife his sea duty required him to carry. Merchant Marine veterans were not awarded veterans’ status until 1988 – technicalities kept Murray from receiving his until 2001 – and at the end of World War II, many mariners were being drafted into the military, their time at sea not counting toward their service requirement. Listen to Hometown Heroes for Murray’s memory of an Army test, why he was singled out for suspicion, and the comical explanation for all of it. Tests at George Washington University would prove no trouble for Murray, who would eventually graduate with Phi Beta Kappa qualifications. “I didn’t get the G.I. Bill,” Lee notes. “So I was working nights and weekends to pay my way through school.” His time at GWU would see his penchant for writing develop, and it was also where he would become a husband and then a father. Murray’s years of research have made him very familiar with discriminatory measures like the Chinese Exclusion Acts, but the story of his personal experience with miscegenation laws is fraught with irony and hindsight humor.

“My birth certificate says I am white,” Murray says, explaining how when his white mother delivered him, Michigan did not have an “Asian” category. “If I marry a Chinese woman, maybe we’ll have problems with that.”

Virginia, where they lived, still had a miscegenation law, barring whites from marrying spouses of other races. Murray and Gladys decided to get married across the Potomac River in Maryland, which did not have such discriminatory rules. They have been married ever since, and Gladys has supported him through a long career in geography and cartography, and his post-retirement passion for discovering hidden history.

Murray next to his plaque at the Mt. Soledad National Veterans Memorial.

The Lees moved to San Diego in 1983, and have been instrumental in the San Diego Chinese Historical Museum since its founding in 1996. Murray has delivered countless public presentations, committed years to painstaking research, and continues to crank out thorough and creatively composed books. In Search of Gold Mountain, published in 2011, details the history and contributions of Chinese in the San Diego area. Through the Eyes of Heroes presents details gathered in Lee’s thorough oral history interviews with Chinese-American veterans around San Diego. You’ll hear Murray speak specifically to the story of Gorman Fong, who survived the Battle of the Bulge, and Victor Schoon, who avoided the Army’s ban on Asian pilots because his father had been mistakenly assigned a German-sounding name when immigrating to the U.S. In 2016, Lee published Elephant and the Indians, complete with colorful illustrations by Mona Mills. “Elephant” was the nickname given to Murray’s grandfather, Lee Yik-Gim, who was captured by a Native-American tribe while working on the Northern Pacific Railroad in the 1880s. Lee is working on another book project now, and he’s hoping that a bill to bestow the Congressional Gold Medal to Chinese-American World War II veterans will eventually make its way to the President’s desk. He is encouraging his fellow Chinese-American vets around San Diego to add their names to the Mt. Soledad National Veterans Memorial, and he hopes the rest of us will understand an important disctinction about the 20,000 Chinese-Americans who served in World War II, and all those who have served since.

“Chinese-Americans are Americans, as well as having Chinese ancestry,” you’ll hear Murray say. “They are willing to fight for their country, and to defend it.”

Hello,

Thank you for posting this interview. Can we republish this story on our website? http://www.themiddleland.com

Also, do you still have a contact of Mr. Murray?

Lillian Zheng

http://www.themiddleland.com