The Holocaust, Witnessed & Remembered

Use controls above or click here to open this Hometown Heroes podcast in a new window

Episode #625 of Hometown Heroes, airing April 23-27, 2020, marks the week of Holocaust Remembrance Day with the memories of three men who came face to face with the inhumane reality of what the Nazi regime referred to as “The Final Solution.” More than six million Jews, and millions more from other oppressed groups, died as a result of the Third Reich’s genocidal campaign before the Allied victory in Europe in World War II.

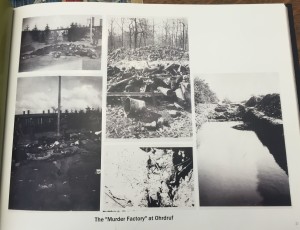

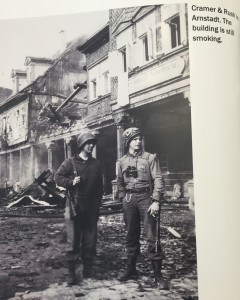

Guard tower at Ohrdruf concentration camp.

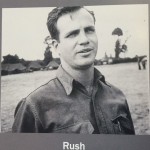

Ohrdruf, a subcamp of Buchenwald, was the first to be liberated, on April 4, 1945. On this episode of Hometown Heroes, you’ll hear the memories of Ralph Rush, one of the first Americans to enter the camp. Rush, whose complete original Hometown Heroes interview can be accessed here, was a 23-year-old with the Intelligence & Reconnaissance platoon of the Headquarters company, 355th Infantry Regiment, 89th Infantry Division.

“We were sent out on patrol one morning, very early,” you’ll hear Rush recall. “We were told we might find something special, but we didn’t know what it was for sure.”

Leading a squad of six men in jeeps, and accompanied by a tank, Rush headed toward coordinates that had been provided from aerial reconnaissance. As the group got closer, they could see a large, fenced in area atop the hill, and headed toward it. They heard a few gunshots as they approached, and when Rush became the first man through the gate, he realized those shots had killed the six men that lay in front of him. Three of them were Americans who had apparently been captured and then executed. Not knowing what they were up against, Rush divided his team into tandems, which broke off to investigate portions of the camp. Among the horrific realities that confronted them was an incineration in progress. Bodies were being burned, with many more on the way to that fate.

“They had been gassed or poisoned, and their bodies were put in railcars,” Rush explained. “Full, absolutely right to the brim. Boxes of bodies.”

Given how small their group was, there was concern that they could be outnumbered by remaining German forces and be in danger. As they tried to fathom the magnitude of the inhumanity, a Polish man who had been imprisoned there approached them. Fighting through the language barrier with hand gestures and a recognizable word here and there, the prisoner explained that some of the captors were disguising themselves in inmates’ clothing in an effort to escape. He was asking for a pistol and ammunition, leaving Ralph with a weighty decision to make.

“I made the decision based on my hunch that he was right,” you’ll hear Rush recall. “So I gave him a gun, gave him some ammunition.”

Soon, the Americans heard shots ring out again, as the prisoner chased down some of those who had carried out the extermination campaign at Ohrdruf. Later, the man returned, crying. He had used every bullet he could find. He offered Rush a silver watch with a long chain as a gesture of his gratitude. Ralph declined, but the man insisted he take it. Ralph intended to bring it back to the U.S., but it was stolen out of his bag before he returned from Europe. Unlike the watch, the images seared into his brain at Ohrdruf never left him.

“The thing that sticks with me more than anything, is the bodies that were being prepared for the burning,” Rush remarked. “There were so many of them, like you might see in a slaughterhouse.”

It was enough to turn his stomach, and Rush and his squad wished they could’ve arrived sooner, potentially sparing the lives of the men they found at the entrance. He couldn’t believe one person could do such a thing to another, he said, and was incredulous at the scale of the Holocaust when so many more camps were discovered and liberated after Ohrdruf. “It’s beyond comprehension,” he said. Once he found the courage to discuss what he had witnessed, he felt an obligation to share the story.

Ralph’s son, John, was his guardian when they visited the National World War II Memorial with Central Valley Honor Flight in 2015.

“The most important thing to me has been for people to find out and know for sure that this is what happened,” you’ll hear him say. “And we can’t stand to have it again.”

Ralph Rush passed away in 2019 at the age of 97. You can access his obituary here, and to read his written account of his experience at Ohrdruf, click here.

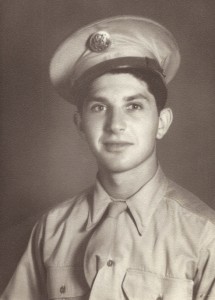

Also featured on this episode is Mel Freedman, a native of Natick, MA and one of more than 550,000 Jewish-Americans to serve in U.S. Armed Forces during World War II. Thanks to his father, he was aware of Adolf Hitler’s virulent anti-semitism long before the U.S. entered World War II.

“My father could understand Yiddish,” you’ll hear Freedman explain. “He could understand an awful lot of Hitler’s ravings, which were carried on the radio.”

That understanding fueled Mel’s desire to fight, and he joined the Army at age 17. After a brief time in the Army Specialized Training Program at Manhattan College, he was sent to infantry training with the 69th Infantry Division. Once he was sent overseas, he was assigned as a replacement with the 45th Infantry Division. In late April 1945, he was tasked with driving Father Kennedy, a Catholic priest, to the recently liberated concentration camp at Dachau, where he couldn’t believe what his eyes beheld.

“Hundreds and hundreds, maybe thousands of bodies, most of them just skin and bones,” he witnessed in a football field-sized mass grave. “You can’t imagine the ovens. We saw human remains in the ovens.”

Even though he spent just a short time in the concentration camp, seeing the deceased victims, the barely alive survivors, and the evidence of what had happened there was an experience that defied understanding.

“I couldn’t conceive,” you’ll hear Mel explain. “Of anybody being that cruel to anybody else.”

Mel Freedman went on to play football for Harvard after WWII. He’s #34 in front row. Robert F. Kennedy is #86 in 2nd row. (Click to Enlarge)

The memories of what he witnessed stayed with Freedman as he returned home after the war and took advantage of the G.I. Bill to attend Harvard University. A linebacker on the Crimson football team, he helped innovate blitzing technique against Brown University, tackling future coaching legend Joe Paterno in the backfield multiple times. He played so well at West Point that Army coach Vince Lombardi came to the Harvard locker room to congratulate him. Robert F. Kennedy was one of his teammates, and he became very good friends with Bobby and his older brother “Jack,” future president John F. Kennedy. You can link to Freedman’s complete original Hometown Heroes here.

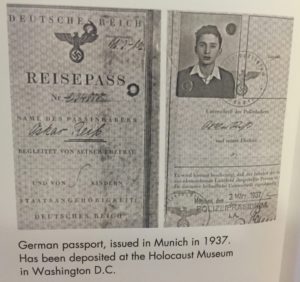

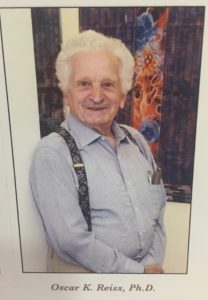

The final World War II veteran you’ll hear on this episode is Dr. Oscar Reiss, who was born in Bad Durkheim, Germany, and raised in the suburbs of Munich. He attended a parochial school until the government forced Jewish children into segregated schools. As Adolf Hitler’s ascent to power picked up momentum, life got progressively more and more difficult for a now teenaged Oscar.

“The Hitler Youth started to really harass me,” Reiss remembered, adding that other Jewish students suffered the same abuse. “They’d throw snowballs at us that had rocks in it.”

They also let the air out of his bicycle tires, and he even remembers being threatened at knifepoint to hand over math tests to Hitler Youth students who couldn’t match his intellect. In 1937, his parents made what would prove to be a life-saving decision for their oldest child. They told 16-year-old Oscar, who spoke zero English, to leave his family behind and seek an education in the United States.

Relatives in the U.S. had connections at the National Farm School (now Delaware Valley University) in Doylestown, PA, and Oscar enrolled there, majoring in dairy science. A professor named Henry Schneider sparked what would become a lifelong affinity for chemistry in Reiss, who first had to pick up a new language. “What helped me with my English,” you’ll hear Reiss explain, “was the head of floriculture had earned his degree at Heidelberg University and was fluent in German.” Within six months, he could communicate fluently, but what little news he received from Germany was not good. His sister, Helene, also made it to America, helped out by family members in Alsace-Lorraine after war broke out in Europe. After finishing the college’s three-year curriculum, Oscar ran a dairy in Ellicott City, MD, but when his sister arrived, he quit that job and moved to Philadelphia to help her. The siblings had each other, but they were completely in the dark as to what was happening to their parents, their younger brother, Wolfie, and their grandparents.

Reiss was initially turned down by the Army because of his “alien” status, but by April of 1943, the tone had changed and he received an induction notice. During infantry basic training at Fort McClellan, AL, a correct response about changing targets quickly on a machine gun caught an officer’s attention. The ensuing conversation revealed Oscar’s fluency in German, which made him a very valuable asset for the war in Europe. Listen to Hometown Heroes for how quickly Oscar was sworn in as a U.S. citizen, and how soon he ended up overseas. The first combat he experienced came in the Battle of the Bulge. He was so close to where he grew up, so close to where his family had been, but still had zero information on their current whereabouts. He thought about them “constantly” as he fought with the 79th Infantry Division. In Germany on March 24, 1945, Oscar spotted a foxhole occupied by German soldiers about one hundred yards away. “I decided to take my radio off,” he recalled of the heavy unit he wore as a backpack, “and crawl on my belly with my carbine.” When he got to within five feet of the foxhole, he sprang up, his gun cocked, and speaking German, ordered the two enemy soldiers inside to surrender. They complied, and Oscar soon discovered something that would prove to be of great value.

“I found a German map that had marked clearly the coordinates of the guns they were using to destroy the pontoon bridge,” he said. “I radioed back immediately.”

Reiss and nearby troops were warned to take cover in their foxholes, as 250mm guns, now armed with accurate coordinates to target, boomed into action. “The shells going overhead sounded like a freight train,” he remembered. The enemy artillery pieces that had been preventing his division from crossing the Rhine River were soon destroyed, and the 79th was able to complete that strategic advance. Oscar’s actions that day would later be recognized with the Silver Star, citing his “complete disregard for his own safety,” as well as his “courage and determined devotion to duty.” Three days later, while looking through binoculars on the front lines, Oscar was wounded when an enemy mortar shell landed less than ten feet behind him. Shrapnel struck his legs and his behind, but “mostly in the radio,” he says. That backpack unit he had removed during his Silver Star exploits this time saved his life.

What if he hadn’t been wearing it? “I’d be dead,” he declares with certainty.

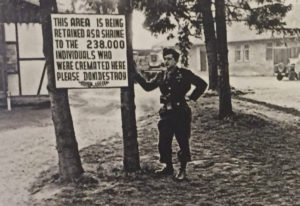

He called for a medic, received first aid, and after recovering for three weeks, found a way to return to his unit, continuing through Germany and into Czechoslovakia. When they passed near the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, word spread quickly among the ranks about some of the atrocities committed there.

Later, Oscar witnessed the haunting aftermath of the liberated camp at Dachau. Eventually, he would come face to face with information about what had become of his family. “I went to Munich where all the records were kept,” he recalled. “I think I knew what I was going to find.” What he discovered was that his parents, his grandparents, and his younger brother, Wolfie, were among the more than six million Jews to die at the hands of the Nazi regime during the Holocaust. He had been asked to use his German language skills as an interrogator of potential defendants in the Nuremberg Trials, but the emotional prospect of dealing with those who had contributed to the murders of his loved ones was overwhelming. Instead, he was assigned to an MP battalion, tasked with finding places for jurors from the Allied countries to stay during the trials. Six weeks later, Reiss was assigned to the U.S. Military Government headquarters in Munich, his childhood home, working in the Information Control Division. Among the projects he worked on were launching a radio station, resuming production at the opera house, and coming up with Germany’s first post-war newspaper, Suddeutsche Zeitung, which remains the nation’s most widely read periodical.

The first edition of Suddeutsche Zeitung, a newspaper Oscar helped launch in post-war Germany.

He remained in Germany until 1947, and as eventful as his first 26 years had been, the rest of his life proved to be nothing short of remarkable. Listen to Oscar’s complete original interview on Hometown Heroes for memories from Oscar’s days at the University of Chicago, where on his way to a Ph.D. in biochemistry over the next seven years, he rubbed elbows with several Nobel laureates, including Enrico Fermi. He taught physiological chemistry at Johns Hopkins for five years, and in 1959 moved to Denver to oversee the biochemistry division at the Webb-Waring Lung Institute at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. He has been on the cutting edge of environmental medicine ever since. In 1961, he worked with two other researchers on a study that showed patients with homozygous emphysema were shortening their lifespan 50% by smoking. It was one of the first published scientific papers outlining the dangers of tobacco smoke. Listen for the moment of “serendipity” that led to his centrifuge helping to solve a problem NASA was experiencing, and also for how he became involved in developing the now ubiquitous screening for prostate cancer, the PSA test.

“It makes me feel proud that I was able to contribute something,” Reiss told Hometown Heroes, crediting his parents for the foresight in sending him to America, and especially his mother for one very valuable piece of advice.

“Get educated,” he remembers his mother exhorting him. “It’s something they never can take away from you.”

Dr. Reiss passed away in 2019, just shy of his 98th birthday.

Hometown heroes

Story of concentration camps.

I wish the host would tell people at the end that this was a direct result of Darwin’s book; “On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favored Races in the Struggle for Life”, If the whole name of his book was always read, one would see where racism originated in the last century. Hitler said in his book “Mine Kompf” that he based his superior race idea on Darwin’s’ book. The “superior” Germans were taught that the Jews, gypsies and others were lower, less evolved animals.

That’s why the German people treated others like animals because they were told they were a lower animal on the evolutionary scale. The lower animals were rounded up and herded into concentration camps, beaten, enslaved, gassed and buried in huge pits. All because of the evolutionary idea that they were lesser animals and the Nazis, the Aryan race, were a perfect and higher race. Hitler followed the evolutionary prime directive: “Survival of the fittest by tooth and claw.”

This has includes the following Communist leaders:

Hitler in the name of Aryan (physical) evolution – Total number of Holocaust victims would be between 11 to 17 million people including 6 million Jews.

Joseph Stalin – Although figures vary, the Soviet civilian death toll probably reached 20 million that Stalin starved or killed to advance Communism (social evolution – i.e. the state evolves into taking the place of God)

Estimate the body count under Mao to be 38 – 67 million. 50 million killed 1924-53, excluding WW2 war losses. Mao’s Great Leap Forward ‘killed 45 million in four years

Pol Pot killed 1.7 million Cambodians to go back to an agricultural society.

[These were gleaned off the internet under the names of the men mentioned.]

Karl Marx wanted Darwin to write an introduction to his book on Communism because Marx based his system on Darin’s book. Darwin said he couldn’t do that because his wife, who believed In God, would not be happy with him endorsing Communism which even then they knew was a godless political movement.

Our Constitution and our dollars say “One nation under God.” Americans who saw the concentration camps were shocked that humans could be so inhuman because of our Judaeo/Christian heritage.

Sincerely Russ McGlenn – Bible and Science Teacher